Franz Xaver Messerschmidt was a German-Austrian sculptor (February 6, 1736 – August 19, 1783) he was born in southwestern Germany and his most famous work is a collection of busts with faces contorted in extreme facial expressions called Character Heads.

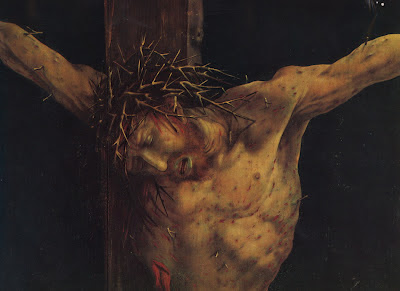

Messerschmidt was headed for a career at the Habsburg court in Vienna until he had a "psychotic break" that denied him advancement and sent him deep inside himself to explore his own (and often extreme) emotional states, which he sculpted in marble, carved in alabaster or cast in lead alloy. Around 1771, as his health apparently deteriorated, he started working on his "character heads", using himself as a model. He created a series of heads with grimacing faces. Collectively, Messerschmidt's "heads" display a range of emotions and, although they are not self-portraits, many resemble the artist.

It is said, to produce these works, the artist would look into the mirror, pinching his body and contorting his face. He then rendered with great precision his distorted expressions. Messerschmidt is known to have produced more than 60 of these astonishing works before he died in 1783 at the age of 47.

It’s been recorded that Messerschmidt was interested in the ‘golden ratio’ and believed that his heads angered the ‘spirit of proportion’ who guarded this knowledge. As a result of this anger, he believed the spirit visited him at night and tortured him. This all sounds fairly delusional, but another explanation could be that perhaps he was just a sufferer of sleep paralysis (hypnogogia).

What happened to him ?

The distortion of the faces seem to reflect the unresolved conflict between his id and his ego, indicating the distorting effect the id has on the ego, and the pressure the id puts on the ego that can lead to its collapse - the ego you lose when you psychotically break with reality and imagine yourself to be persecuted by demons. Messerschmidt could not find a socially and artistically respectable way of containing his id, which is why the expressions on the faces of his character heads seem disrespectful and anti-social, in some cases provocative.

His madness proved to be strangely liberating. Leaving cosmopolitan Vienna for his provincial hometown. He began to make art that was true to himself, art that was as mad as he was. Returning to the place of his birth, he was reborn as an artist, a strange one, no doubt, but no longer a stranger to himself, as well as a person. He had become authentic, socially as well as artistically, someone wearing an unpretentious hat rather than a self-glorifying wig. Sculpting his mad face, the face he found when he lost face, when he was stripped of his social mask, when his star had fallen, he became a True Self. His demons were now his muses, and he made the creative best of them by portraying them. He had to, because they never disappeared from his mirror. The faces constantly changed, but they all looked inward, fascinated by their own madness. Messerschmidt took pleasure from his madness, the pleasure he denied himself during his painful ascent to the social heights of art, the pleasure in life he forfeited when he aspired to become a great artist and be recognized as such by society, the pleasure that his ambition deprived him of, pleasure that finally became the strange pleasure of madness, for he seemed to enjoy making faces at himself.